Some foods are just food. And some foods feel like a dare, a challenge, a cry for help. Iceland’s national dish, hákarl, is firmly in the second category. It’s fermented, borderline-rotten Greenland shark, buried in the ground, peed on (metaphorically, by itself), and then hung to dry for months until it reeks of ammonia and regret. The taste has been described by celebrity chefs as “the single worst, most disgusting and terrible tasting thing” (Anthony Bourdain) and like “chewing a urine-infested mattress” (Ainsley Harriott). Gordon Ramsay couldn’t even keep it down.

So, the question isn’t just why do people eat this? The question is, what kind of collective historical experience, what level of national trauma, leads to a country embracing fermented, poisonous shark as a beloved delicacy? Is hákarl just a weird food, or is it the culinary embodiment of surviving the impossible? Let’s take a deep dive.

First, you need to understand Iceland. It’s a volcanic rock in the middle of the North Atlantic. For centuries, survival here was brutal. The winters were long, dark, and unforgiving. The land couldn’t grow much. The sea was their only real source of sustenance. And one of the biggest things in that sea was the Greenland shark.

There was just one tiny problem: the Greenland shark is lethally poisonous when fresh. It doesn’t have a urinary tract, so it filters waste through its flesh. This means its meat is saturated with incredibly high levels of urea and trimethylamine oxide (TMAO). Eating a fresh piece of it would, at best, make you violently ill. At worst, it could cause blindness or death. So, for centuries, this massive, abundant source of protein was just swimming around, completely inedible. It was a cruel joke from Mother Nature.

At some point, probably out of sheer, desperate necessity, the Vikings in Iceland figured out a way. It wasn’t pretty. It wasn’t elegant. But it worked. The process they developed is a masterclass in turning poison into protein.

Step

The Process

The Science (Why It Works)

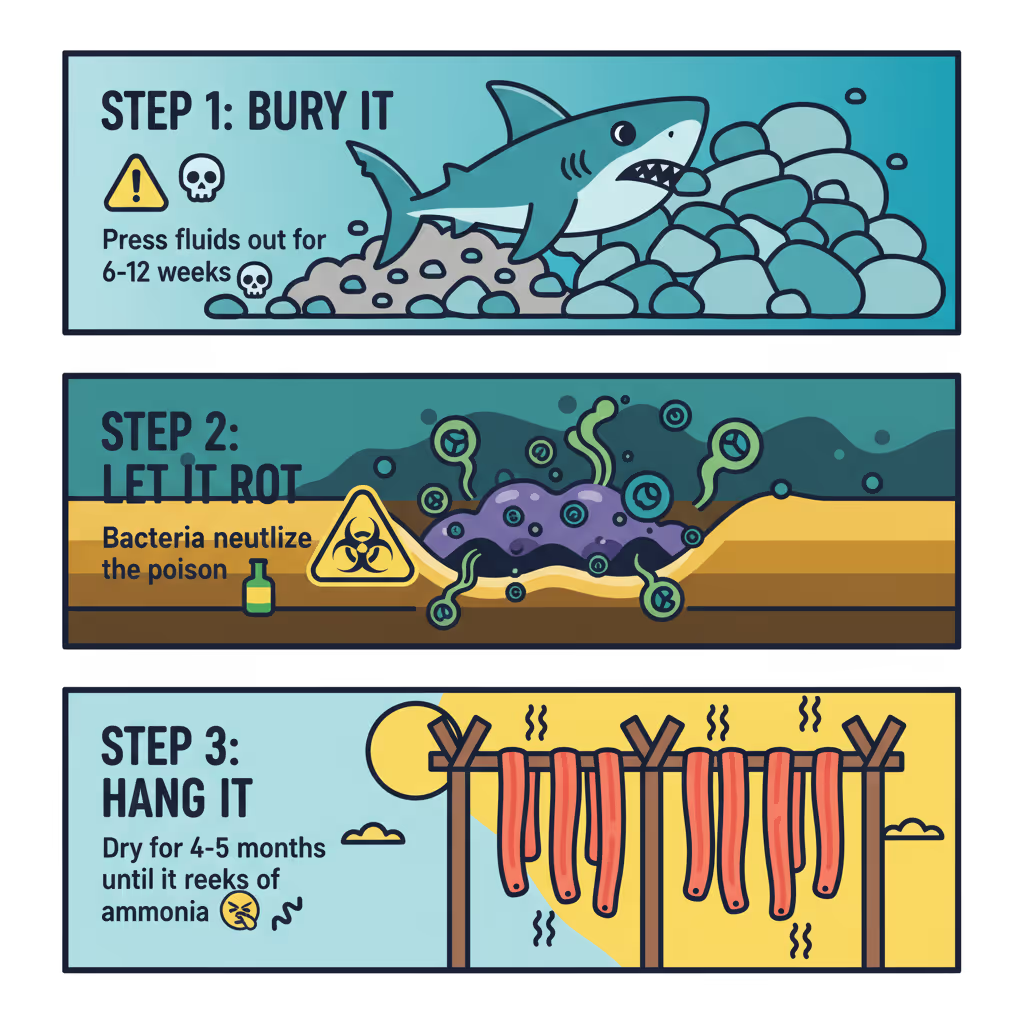

1. Bury It

The shark is beheaded and placed in a shallow gravel pit. It’s then covered with more gravel and heavy stones to press the fluids out.

The pressure squeezes out the poisonous liquids. The cool, dark environment allows fermentation to begin without putrefaction.

2. Let It Rot

It’s left to ferment underground for 6 to 12 weeks.

Bacteria break down the urea and TMAO, neutralizing the toxins. This is where the signature ammonia smell comes from.

3. Hang It

The now-fermented shark is dug up, cut into strips, and hung in a drying shed for 4 to 5 months.

The open-air drying process allows the ammonia to dissipate slightly and concentrates the flavor. A dark crust forms, which is removed before eating.

This isn’t just cooking; it’s a science experiment born from desperation. It’s the culinary equivalent of being trapped on a desert island and figuring out how to drink seawater. You do it because you have no other choice.

Eating hákarl today is a completely different experience. It’s no longer about survival. It’s about tradition, identity, and maybe a little bit of tourist-shock value. It’s served in tiny cubes on toothpicks, often during the midwinter festival of Þorrablót, and chased with a shot of a potent Icelandic schnapps called Brennivín (nicknamed “Black Death”).

First-timers are advised to pinch their nose, because the smell is overwhelmingly pungent, like a bottle of industrial-strength cleaning fluid. The texture is chewy and rubbery. The taste? It’s a complex wave of intensely strong fish, nutty notes, and a lingering aftertaste of ammonia that kicks you in the back of the throat. It’s a food that makes you feel alive, mainly because you’re so acutely aware that you’re not dying.

In a way, yes. Hákarl is the story of Iceland itself. It’s a story of taking something deadly and unforgiving—a poisonous shark, a barren landscape—and through sheer ingenuity and resilience, turning it into a source of life. It’s a dish that says, “We survived this. We can survive anything.”

Every cube of hákarl is a bite of history. It’s a taste of the harsh winters, the isolation, and the unyielding spirit of a people who refused to be beaten by their environment. It’s a national dish that doesn’t just taste like fish; it tastes like victory. And maybe a little bit like a urine-infested mattress. But mostly victory. 🔥

1.Wikipedia - "Hákarl" The go-to source for the complete breakdown of the preparation process, the science behind the toxicity, and the cultural context of hákarl as part of the Þorrablót festival. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hákarl

2.Your Friend in Reykjavik - "The Fermented Shark of Iceland" A great blog post that covers the history of shark hunting in Iceland, the dangers of the fresh meat, and practical advice for trying it yourself (like not opening it in your hotel room). https://yourfriendinreykjavik.com/fermented-shark-iceland/

3.Atlas Obscura - "Hákarl" Known for celebrating the world’s weirdest wonders, Atlas Obscura provides a fantastic, concise summary of hákarl, complete with visceral descriptions of its taste and smell from those who have dared to try it. https://www.atlasobscura.com/foods/hakarl-shark-iceland